Pava | Red Phoenix correspondent | Florida–

The experience of Puerto Rican resistance to American imperialism serves as an immensely inspiring example to oppressed peoples in the U.S. and around the world in their struggle for a truly democratic, socialist society. One of the most important series of events in this history of resistance were the Sugar Strikes of 1933.

The American Sugar Monopoly

To fully understand the strike, we must understand the history behind its cause. The United States seized the island of Puerto Rico from Spain after their victory in the Spanish-American War in 1898. By the 1930’s, the Puerto Rican economy was primarily based on the export of agricultural goods, namely sugar and tobacco. At least 70% of Puerto Rico’s arable land was owned by U.S. corporations such as the South Porto Rico Sugar Company, Fajardo Sugar Company, and Central Guánica. These corporations relied on jornaleros (day laborers) and would hire them seasonally and pay them next to nothing.

This was only made worse by the Great Depression that destroyed the sugar industry. To save their precious profits, these American corporations would fire en masse, and the workers that remained had their wages cut and working conditions drastically worsened. The average wage went from 90 cents to 50-60 cents in 1931-32, while cost of living rose one-third above the average. Malnutrition, poor sanitation, lack of sewage systems, and dangerous working and living conditions were common. These horrid conditions led to higher mortality rates due to workplace accidents and diseases, such as dysentery, diarrhea, malaria, and tuberculosis.

As the sugar workers were barely living, some sugar companies continued to gain impressive profits; for instance, Fajardo Sugar tripled its profits from 1931 to 1932. A classic example of the horrid inequalities between the bourgeoisie and proletariat, especially in the colonial context.

The Sugar Strike of 1933

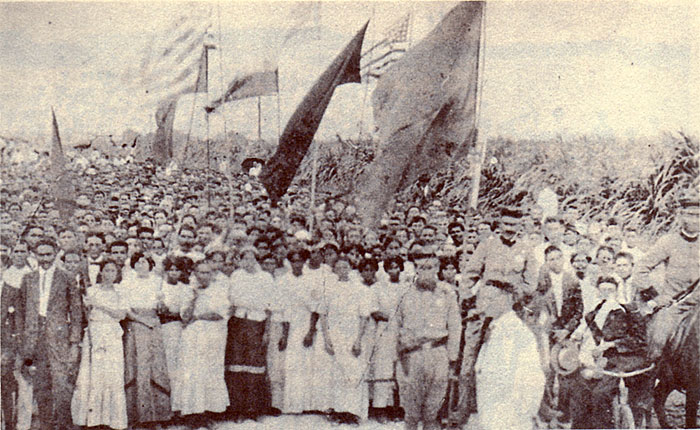

Radicalized by this capitalist crisis, during the period of 1933-34, about 50,000 sugar and mill workers mobilized mass strikes across the island in what became the largest organized strike in Puerto Rico up to that point. Initially, the strikes were isolated and small but rapidly grew and spread across the island; namely in the towns of Ponce, Barceloneta, Aguada, Moca, Guánica, Yabucoa, Fajardo, Maunabo, Dorado, Guayama, Salinas, and Santa Isabel. The strikers demands included a wage raise to $1.50 a day, an 8-hour workday, and improved housing conditions.

The Colonial Reaction

Despite their overwhelmingly peaceful nature, the American response to these strikes were severe and repressive, The American government, in the interests of capital, deployed the Insular Police, a colonial paramilitary force under American control, and the United States National Guard to the cities most affected by the strikes; Most notably, the cities of Ponce, Yabucoa, Guánica, Aguadilla, and Caguas. These forces used live ammunition and tear gas against protesters. In response to the repression, the protesters attempted to defend themselves by throwing stones against the militarized forces.

The official records of how many workers were killed or injured are unclear since most of the reports were censored, incomplete, or weren’t even reported at all by pro-imperialist news sources and authorities.

Amongst the strikers, hundreds of workers were arrested, and their trials were tried by US-appointed judges and were conducted only in English, which most of the arrested didn’t understand. Additionally, most of the arrested were denied defense attorneys, or had attorneys with little time to prepare their defense. The accused were also blacklisted by their previous employers; their only crime being their desire for human dignity.

The Reformists’ Betrayal

During the strikes, the reformist socialist parties of Puerto Rico would reveal themselves to be lackeys of the US imperialists. One of the major parties of reformism, the Socialist Party of Puerto Rico (Partido Socialista de Puerto Rico, PSPR), distanced themselves from the strikes and outright condemned them, calling them “irresponsible” and “disruptive.” The leader of the PSPR, Santiago Iglesias Pantín, had this to say: “Irresponsible agitators cannot be allowed to disturb public order under the pretext of defending workers’ rights.” (El Mundo, June 2, 1933)

The FLT and Pedro Albizu Campos

In January 1934, the Free Federation of Workers (Federación Libre de Trabajadores, FLT), the largest trade union associated with the Socialist Party of Puerto Rico, reached an agreement with the island’s comprador government that increased the sugar workers’ daily wage to 90 cents. The FLT considered this a victory and ordered the strikers to demobilize, but the strikers refused this pathetic compromise and demanded their wage to be increased to $1.50 per day, which was already barely a livable wage. This rejection by the striking workers further discredited the reformists and revealed that they will actively disregard the interests of the workers and side with the capitalist-imperialist class in the midst of the class struggle. Without a militant vanguard working class Party, the strikers turned to Pedro Albizu Campos, one of the most famous leaders of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico (Partida Nationalista de Puerto Rico, PNPR) to guide their actions. As a progressive petit-bourgeois revolutionary with close ties to the worker’s movement, Campos travelled around the island making fiery speeches to thousands of strikers urging them to continue to strike, confronting capitalist, racist and colonial oppression.

The Formation of the Worker’s Party

With the weakening of the reformists’ grasp on the labor movement and the rising class-consciousness of the Puerto Rican working class, on September 23, 1934, in the city of Ponce, several Marxist-Leninist organizations merged to form the Puerto Rican Communist Party (Partido Comunista Puertorriqueño, PCP). The PCP’s formation significantly re-directed the working class movement in Puerto Rico to a more militant and revolutionary direction. It also allowed for a more consistent internationalist outlook to grow in Puerto Rico, gaining support from the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), the Communist Party of Cuba (CPC), and the broader Communist International.

Synthesis

The Sugar Strikes of 1933-34 were a pivotal historical development in the anti-imperialist and workers’ movements in Puerto Rico. The strike’s critical failure was due to its lack of disciplined, proletarian leadership that would take their interests seriously and fight for them without capitulating. Their reliance on the leadership of the cowardly and opportunist reformist Parties ultimately doomed the strike. However, this failure provided much needed revolutionary experience and practical lessons for the Puerto Rican working class movement that then paved the way for the formation of the PCP! The setbacks and failures of the strike provide a vital lesson to not only the Puerto Rican worker, but to all peoples who suffer under the yoke of capitalism-imperialism.

Reformists and traitors be damned!

Long live the struggle for the happiness and freedom of mankind!

¡Gloria a la Partida Americana de Trabajo!

Bibliography:

- Ayala, César J. American Sugar Kingdom: The Plantation Economy of the Spanish Caribbean, 1898–1934. University of North Carolina Press, 1999, pp. 205–243.

- Ayala, César J., and Rafael Bernabe. Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History Since 1898. University of North Carolina Press, 2007, pp. 157–159.

- Caban, Pedro A. Constructing a Colonial People: Puerto Rico and the United States, 1898-1932. Westview Press, 1999.

- Carr, Raymond. Puerto Rico: A Colonial Experiment. New York University Press, 1984.

- Dietz, James L. Economic History of Puerto Rico: Institutional Change and Capitalist Development. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Figueroa, Luis A. Sugar, Slavery, and Freedom in Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

- Guerra, Arcadio. “La lucha obrera y el Partido Socialista.” Puerto Rico: Ensayos de historia social. Siglo XXI Editores, 1988, pp. 139–140.

- Lauria Santiago, Aldo. Collective Action and Labor Politics in Puerto Rico, 1932–1939. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994, pp. 48–49.

- Santiago-Valles, W. F. Subject People and Colonial Discourses: Economic Transformation and Social Disorder in Puerto Rico, 1898-1947. State University of New York Press, 1994.

- Scarano, Francisco A. Puerto Rico: Cinco siglos de historia. McGraw-Hill Interamericana, 1993.

Categories: History, International, Labor, Puerto Rico, Revolutionary History, U.S. News