(Editor’s Note: Disney has just announced that they are waiving their right to arbitration only after mass outrage and pressure from media coverage. However, that Disney was able and willing to force arbitration in such a way is still cause for alarm, as online accounts and terms of service agreements are increasingly unrealistic for consumers to avoid –or to thoroughly read and understand before accepting– in this digital era.)

Eris Rosenburg | Red Phoenix correspondent | Minnesota–

A widower may be prevented from filing a lawsuit over the death of his wife because he once signed up for Disney’s streaming service.

On January 22, 2024, Mr. Jeffrey Piccolo filed a wrongful death claim against Great Irish Pubs Florida, Inc. and Walt Disney Parks U.S., Inc. in Florida’s Orange County Circuit Court following the death of his wife, Dr. Kanokporn Tangsuan.

According to the facts of the case, Dr. Tangsuan passed away after being served food at a restaurant in Walt Disney World which contained ingredients to which she was allergic. This comes despite the fact that Dr. Tangsuan repeatedly notified the server of her dietary restrictions.

While negligent food handling is an unfortunately common scenario in civil law, there is one aspect of the case that is highly unusual. At the center of recent controversy in the bourgeois media is a claim made in Walt Disney Parks and Resorts (WDPR)’s Motion to Compel Arbitration and Stay Case, filed on May 31, 2024. The motion makes the argument that the Court should force Mr. Piccolo to agree to settle out of court, given the mandatory arbitration clause which he agreed to when he created an account with the Disney+ video streaming service. That clause allegedly states that he agreed to arbitrate all disputes “against the Walt Disney Company or its affiliates… arising in contract, tort, warranty, statute, regulation, or other legal… basis.” As heartless as it is, this attempt to use an unrelated technicality to throw out Mr. Piccolo’s lawsuit is not a new phenomenon within the U.S. legal system.

The role of “Zealous Advocates”

As the spokespeople for Capital, bourgeois legal analysts commenting on this case will no doubt point to the fiduciary duty of attorneys to “zealously advocate” for their clients – in other words, to throw claims at the wall until one sticks in court. On first glance, this axiom seems to ensure that both parties to a lawsuit exhaust all available legal justifications for their actions in a case, thereby promoting the discovery of so-called legal truth, and the symmetry of court decisions and legislation. In practice, however, it also leads to the unending generation of pretenses that the American bourgeoisie can use to excuse its exploitation of the working masses both domestically and abroad.

Moreover, attorneys and judges have an explicit duty as agents of the capitalist legal system to uphold their profession as part of the bourgeois societal superstructure, and an unspoken one to reinforce the economic relations of its base. Nowhere is this unspoken duty more evident than in the constant justifications that they find for limiting the compensation that can be sought from their capitalist masters: that penalties against companies should be limited so as not to harm their workers and wider community, that corporations should be considered fictional persons to protect their officers and shareholders from liability, and so forth.

As reactionary and antisocial as WDPR’s justification for obstructing Mr. Piccolo may be, the reality is that it is much worse than a first glance would suggest. To understand the real implications of Disney’s claim, we must briefly look at the U.S. legal system.

Overview of the U.S. Legal System

The United States legal system falls within the category of “common law,” founded in the United Kingdom and still used today in some of its former colonies. Common law relies heavily on the precedent of previous court decisions through the principle of stare decisis (“to stand by things decided”). This principle alleges that by allowing the ghosts of the past to guide in present decisions, courts can reach predictable, coherent outcomes when the facts of a past and present case are similar. It should be noted that this is precisely where the wider danger in Disney’s argument originates.

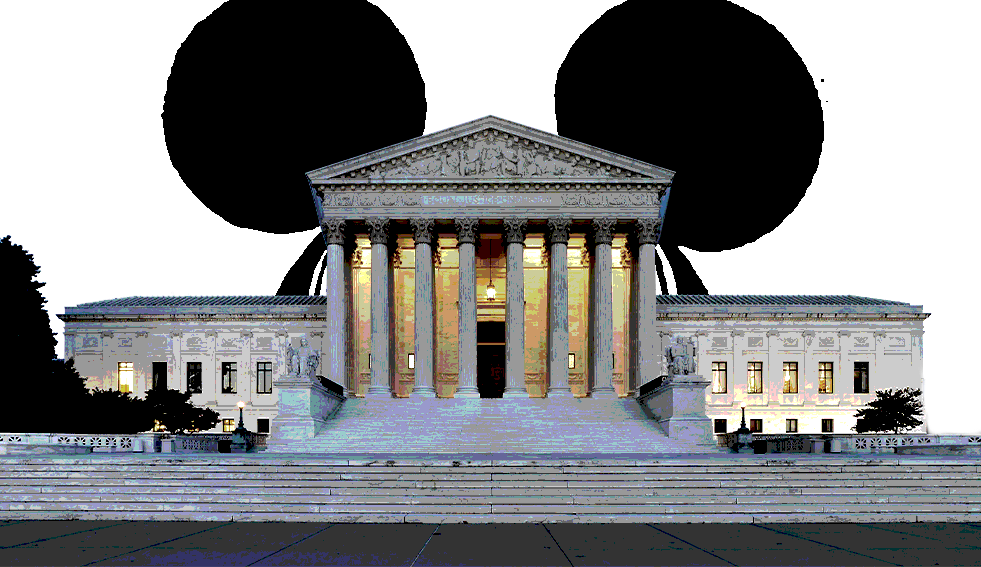

Under common law, precedent can be divided into two types: binding, and persuasive. Binding precedent refers to decisions which the deciding court and all courts below it within its jurisdiction must follow, whereas persuasive precedent refers to decisions that courts of equal standing or in different jurisdictions do not need to follow but may reference when coming to a decision. A typical flow of binding authority in the United States court system can be seen in Figure 1 below:

Similarly, a party to a lawsuit who wishes to appeal the decision rendered on their case by a court generally has to follow the flow shown above. This relationship of binding authority to the appeals process is important, because it shows the progressively wider reach the verdict for a given case will have on legal precedent as it is appealed to higher and higher courts.

As the reader can see, there is the possibility that the reactionary claim made by Disney’s attorneys could affect the entire state of Florida, or even the country as a whole if the case is appealed. In the words of Mr. Piccolo’s representation in its response to Disney’s motion: “In effect, WDPR is explicitly seeking to bar its 150 million Disney+ subscribers from ever prosecuting a wrongful death case against it in front of a jury even if the case facts have nothing to with Disney+.” Depending on the verdict reached in the case, we are facing the possibility that a mandatory arbitration clause for a single service provided by Disney has the effect of barring any sort of legal action against them under any circumstances. Yet, the implications of this argument go even further.

Mandatory Arbitration Clauses

Mandatory arbitration clauses are a staple of contract law in the United States today. Originally introduced in the Federal Arbitration Act of 1926, they can now be found anywhere from simple sales and housing rental contracts, to credit card and employment contracts, to major deals brokered between large firms. It is not an understatement to say that it would be impossible to track how many mandatory arbitration clauses each worker has agreed to throughout their life.

Even more concerning than these arbitration clauses’ ubiquity is the method by which they operate. These clauses waive the ability of the parties to the contract to sue in court, instead committing both parties to the process of arbitration in the event of a disagreement: a process by which a third party examines the facts of the disagreement and decides what the appropriate solution, if any, is. Common wording in an arbitration clause states that the provider of the service involved gets to decide the following:

- The location where the arbitration will take place and corresponding binding law;

- The presiding arbitrator or arbitrators, in practice a former judge(s) that may in fact have previous associations with the service provider;

- The time limit in which a dispute must be filed; and

- Whether or not there is an appeal process.

The ability of a service provider to choose which law binds the contract is not an accident. The jurisdictions frequently known as ‘tax havens’ do not just benefit the financial filings of capitalists; they often also have a lower level of workers’ protections, and more corrupt legal systems that further amplify the power disparity between bourgeois and proletarian. In the United States, examples of these jurisdictions that may frequently appear in arbitration clauses include the States of Delaware and Florida, among others. Claimants who have never stepped foot in these places often find themselves obliged spend vast amounts of time and money to travel or to retain legal counsel of questionable sympathy in faraway jurisdictions just to participate in the arbitration process. For the working masses who cannot afford to take time away from their jobs, much less spend last sums on representation, this is an unbearable pressure.

A final consideration on WDPR’s argument in its Motion to dismiss Mr. Piccolo’s case is its wording in the phrase “…or its affiliates.” Here, its attorneys make the argument that because he agreed to a single clause for a single service of a single company, he is unable to sue Disney or any of its subsidiaries, or perhaps even any company it does business with. Given the high concentration of Capital in the United States and subsequent web of ownership and business relations each company has (especially large corporations), the question arises as to who would not be subject to a mandatory arbitration clause over every possible legal claim, if Disney’s argument was validated in a higher court.

As shown above, it is characteristic that the bourgeois legal system attempts to maintain a thin veneer of equality and fairness while at the same time protecting its ruling class from liability through endless mazes of technicalities and barriers. Disney’s argument represents a bourgeois attempt to add another, nearly impenetrable, layer of obstacles to prevent the working classes from using its legal system.

Synthesis

In the above-mentioned lawsuit, we are glimpsing yet another portent of the present, ever-accelerating decay of American capitalism. What appears at first to be an underhanded ploy by a team of attorneys to win against a grieving husband is also an attack on the working masses as whole. If Piccolo, Jeffrey vs. Great Irish Pubs Florida, inc. et al. were to make its way to the Supreme Court, all custodians of American Capital, including three who were appointed by fascist figurehead Donald Trump, a foreseeable long-term result would be the near-complete destruction of bourgeois civil law as we know it. The scope of the decision could be expanded to encompass every company and concern operating in the United States that has ever included a mandatory arbitration clause in one of their contracts, as well as their subsidiaries and other affiliated companies. Swathes of workers would be unable to seek even the most basic level of compensation for injuries or deaths arising from corporate negligence and malfeasance. It is the duty of communists across the U.S. to decry this development.

As Capital tightens its noose around the neck of the working class, we can find no savior from antisocial legalism in either of the major bourgeois parties. Both merely serve different sections of the American capitalist class and have shown their dedication to decreasing concessions made to the workers while ramping up exploitation. Instead, we must educate, agitate, and organize under the banner of a proletarian vanguard party.

Chicago’s budget crisis as case study for necessity of socialism

Chicago’s budget crisis as case study for necessity of socialism  Crisis in the bourgeois legal system

Crisis in the bourgeois legal system  SCOTUS rules in favor of return to smog-choked cities, burning rivers

SCOTUS rules in favor of return to smog-choked cities, burning rivers