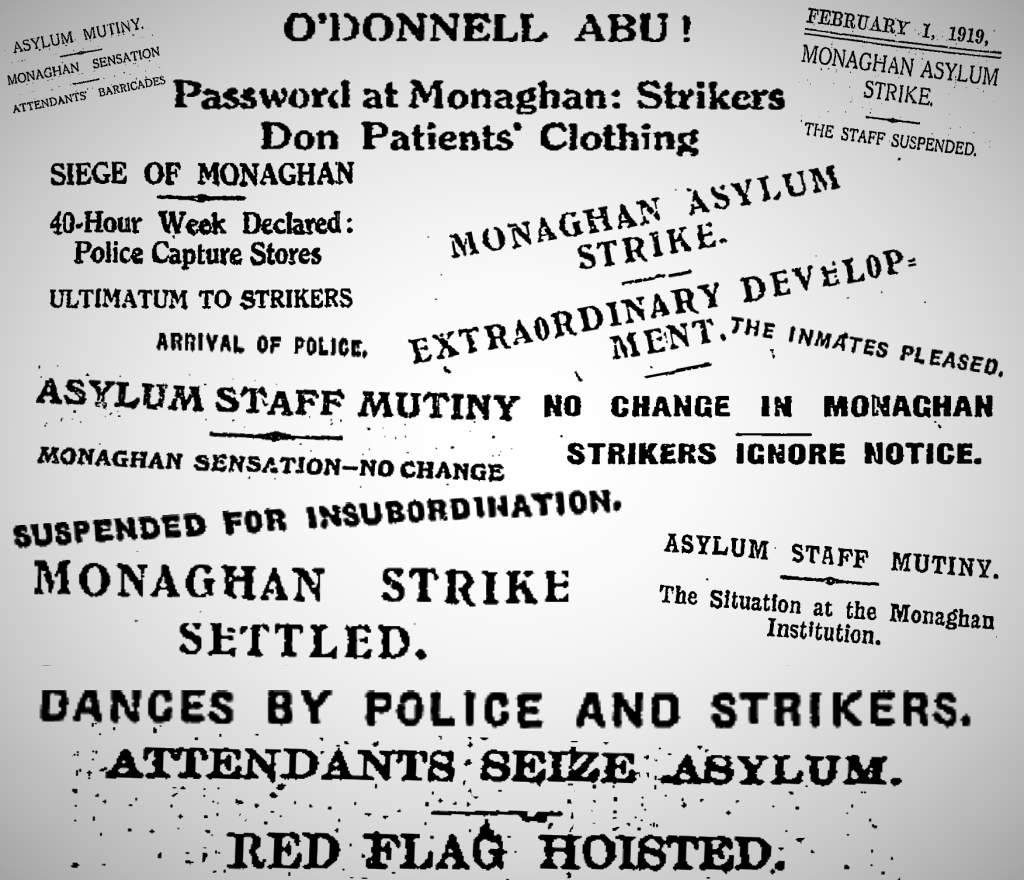

On Jan. 24, 1919, the red flag was raised over the Monaghan Lunatic Asylum, the first Soviet of the wider Irish Revolution, and one of the first Soviets declared outside of Russia. Much less well known than the Limerick Soviet, which is often referred to as the first of the Irish Soviets despite being chronologically later, the Monaghan Soviet is a unique and interesting case of an uprising within a psychiatric hospital.

The Monaghan Lunatic Asylum, now the St. Davnet’s Hospital, was established in 1869, shortly after the Lunacy Act of 1867 was passed. This law made the indefinite incarceration of “dangerous lunatics” in psychiatric hospitals substantially easier. Consequently Ireland had one of the highest per capita number of inmates in psychiatric institutions in the 20th century. To be considered a “dangerous lunatic” one did not even have to commit a crime or provide evidence of dangerous behavior. Some patients were admitted for behaviors including social unrest, alcoholism, syphilis, jealousy, as well as what we would now call depressive or anxious states.

The events that led to the declaration of the Soviet began with a strike in 1918. Hospital staff were often working 93-hour weeks with up to 13 days between rest days and were often disallowed to go home between shifts, instead being forced to stay on the property. All the while, they worked for a meager pay of 60-70 pounds per annum (roughly 3,800 pounds in today’s currency). The Soviet was declared on Jan. 24, 1919, led by Peadar O’Donnell, a labor organizer and Irish Republican. A significantly reduced 48-hour work week was announced, and 125 police then barricaded the fledgling Soviet.

“From my own time in mental hospitals, there is a certain level of comradery between the patients and the staff. There are, of course, staff who seem to hold a great deal of disdain for us, and the staff as a whole do carry immense power over the patients, but there are also many who deeply care for us and want to do at least what they believe is best for us. However, much like we are trapped in bindings by the state, our families, and “best practices,” they are trapped in their own bindings by administration and capitalism. They are overworked, and underpaid, and given few resources to actually make the changes they feel would benefit patients.”

Unfortunately, available information on the events inside the Monaghan Soviet is limited, often relying on third- or fourth-hand accounts for all but the most basic details. Though some stories of the events of the Soviet say that in preparation for a police siege, patients and staff exchanged clothing to sneak in supplies and to confuse police, and had a level of equality and participation of the patients.

“When you are a patient in a mental hospital, you often have very little say in what happens to you. In the best case you may be given choices of how to proceed, but there is a very clear power dynamic between you and the doctors. They are in charge and they hold in their hands how things will go for you. Many times, you are not given any choice at all. Do what it is you are told or things will get worse for you. Even then, what we have now is far, far better compared to conditions a century ago. It is hard to imagine how liberating it would have been for the patients of that hospital to suddenly have a genuine say in their lives and hope for a better future.”

Authorities initially offered the desired pay raises to only the men. However, standing in solidarity, this offer was rejected. Authorities would eventually relent, granting pay raises to both male and female staff, a reduction to a 56-hour work week, and permission for married staff to return to their homes between shifts. On Feb. 4, 1919, the Soviet ceased to exist and operations returned to normal.

It is an unfortunate reality that even after the revolution, hospitals will still need to exist for those with higher support needs. However, when re-imagining care under a new socialist system, the events of the Monaghan Soviet should not be forgotten. We should seek to devise a system which not only prioritizes patient wellness and staff working conditions, but participation of both the patients and staff as equals in their own “Lunatic Soviets.”

Categories: History, Revolutionary History, World History

The Fall of Lin Biao

The Fall of Lin Biao  The Communists and the Bolivarian process

The Communists and the Bolivarian process  The myth of Stalin’s ‘demoralisation’ in 1941

The myth of Stalin’s ‘demoralisation’ in 1941  Remembering the Italian partisans who ended Mussolini’s violence

Remembering the Italian partisans who ended Mussolini’s violence