By Sofia D., Red Phoenix correspondent, Minnesota.

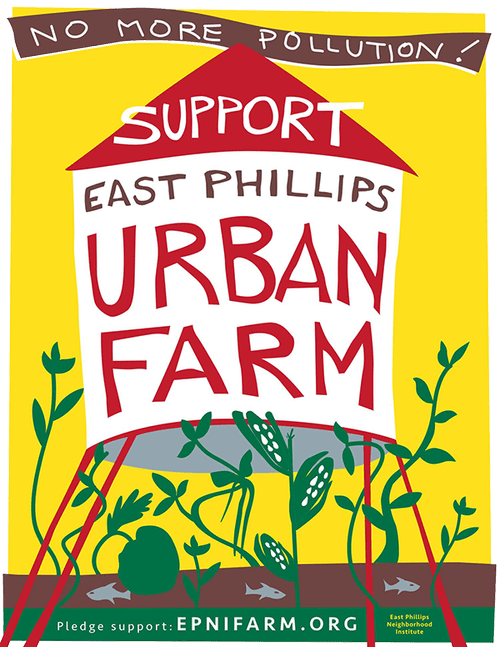

In 2023, the East Phillips Neighborhood Institute (EPNI) in Minneapolis will purchase the Roof Depot, a vacant lot named by its most recent corporate inhabitant. EPNI is run by activists as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, with all of its tax statements easily accessible. The city had planned to demolish the lot, to which activists, especially from the American Indian Movement, objected on the grounds that demolition presents an undue risk to the neighborhood, with arsenic from the factory’s pesticide-producing past being easily dispersed onto the neighboring, largely Black, Indigenous, and Latino community. As a counter-proposal, the EPNI has put forth a vision of the abandoned Roof Depot repurposed as an urban garden, with ownership being distributed equally between tenants, residents, and outside investors. The leaders of this initiative are all respected activists within the community, and the project will undoubtedly bring low-cost housing, many decent jobs, and yet another environmentally sound and sustainable urban garden to Minneapolis. The ability of the EPNI to buy this property was the result of a 9-year battle with the state, mobilizing many sectors of the working class, especially oppressed national minorities, to gain this truly monumental concession.

Unfortunately, fighting for concessions from capitalists only ever results in short term gains. In 1799, Robert Owen purchased the New Lanark mill, intent on realizing a vision of industry untainted by the evils of capitalism, with dignity for its workers, and a plan for a new world dominated by rationality and kindness. His plans for a moral factory succeeded, and the condition of his workers was improved greatly. This mind of genius had brought the end of suffering under capitalism! Utopian, rational socialism was the new era of industry – now for the task of convincing the world.

Robert Owen’s vision failed. In place of dignity, we have dirt on our hands and face – not the lush dirt of a society that takes care of its land, but oil and dust. In place of a decent salary, we have pennies. In place of a stable living, we have a “gig economy.” Our bodies are disposable, replaced by whoever sells themselves at the cheapest price. The profit motive won out because monopoly has made it impossible for any business to survive the beginning stages without heavily exploiting its workers. Highly exploitative, incorporated businesses are more profitable, more stable, and attract more investment. If a bank loan is needed to start a business, an investment of just 40% is enough to give the bank power over the business, which enables them to pressure the business to become more profitable, more exploitative. In addition to these structural factors, Robert Owen was the exception – most capitalists have no such moral convictions, because keeping a business alive with such convictions is all but impossible due to the competition that monopoly prices provide. The fundamental mechanisms of capital keep such “moral” enterprises underwater, struggling for air. So it is with nonprofits. So it is with co-ops. So it was with Robert Owen’s utopian societies.

Now, this does not mean that the achievements of EPNI are meaningless. EPNI will provide incredibly important services to the local community, including job and housing opportunities for oppressed and exploited workers. It will provide a lively hub of economic and cultural life for the neighborhood, and a sorely needed source of quality food. But this cannot be the end goal. The EPNI’s urban gardening project will be under constant threat throughout the entirety of its existence – of bankruptcy, and of sabotage. Investors and the market will constantly pressure it to change missions, to provide them profit even when the owners themselves are receiving only a modest wage. EPNI is doomed under capitalism to the same fate as the New Lanark mill. Now there are some important differences: EPNI has the entire community behind it, and is run in a city where voices sympathetic to working-class struggles poke through the noise of capitalist complacency in the local government just often enough that they may survive and thrive for many years to come. But this is no guarantee of continuity, and EPNI and its community must remain vigilant in placing people before profits.

But the EPNI, like the New Lanark mill, is still fundamentally built upon a capitalist framework. The representation it promises workers and tenants is not guaranteed by law, and so it is liable to be eroded, if not outright illusory. A “nice” capitalist still has to turn a profit, and to do that, it must exploit workers by paying them for only a fraction of the labor they produce. Representation is not the same as power, and although workers at EPNI might have representation, they will not have the real power to serve their real interests. Socialism cannot be built through more co-ops, unless they are built on a real framework of workers’ power, rather than a token one. This real framework is referred to by Lenin as dual power.

Dual power does not mean the gradual replacement of openly undemocratic capitalist enterprises with democratic capitalist enterprises, but the establishment of socialized mechanisms of production, distribution, and governance which vie for legitimacy with capitalist institutions. Such socialized institutions operate independently of the official channels, although within legality in the early vulnerable stages, and disseminate and fortify the workers’ struggle for full power in society. The Black Panthers, with their breakfast program, literacy and education programs, and community patrol, represent a powerful attempt at establishing dual power in the United States. Systems of dual power might look very similar to cooperatives, in that workers and members have some say in production and distribution, but are fundamentally different: dual power is a building block of a socialist economic system, while cooperatives are simply a feeble attempt to “humanize” the fundamentally unchanged capitalist economic system. They both have a democratic element and appear similar on the surface, but in cooperatives, the democratic element is a fleeting, surface level phenomenon, with real power lying in the hands of the capitalist class – in systems of dual power, the democratic element is representative of complete proletarian control, of the embryo of an economic system driven not by anarchic production and profit motives, but by stable prosperity based on production and distribution by need.

If the EPNI continues on its path of striving for capitalist concessions, it will dampen the class consciousness of its workers and tenants and develop an internal oligarchy, representing bourgeois class interests. It will demand reform, reform, reform, and position itself as the ultimate solution to the contradictions within capitalism. In this scenario, it will lose the trust of the workers, and slowly fade out of political life. Absorption is a much more straightforward fate – rather than a slow rot from within, the EPNI would be taken over by capitalist forces, whether through the selling of stock, or the appointment of new, non-activist directors, or even through a forcible takeover by the state. In any of these cases, the EPNI will lose the remarkable opportunity placed before it to become a true bastion of internationalist workers’ solidarity, and an arm of dual power.

So the tasks before the EPNI are twofold: first, to meet the immediate material demands and needs of its community, and second, to channel that community connection into a source of proletarian dual power, rather than continuing along the path of reformism.

Categories: U.S. News, Workers Struggle

Striking workers shut down 21 ports in solidarity with Palestine

Striking workers shut down 21 ports in solidarity with Palestine  Interview with People’s March organizer on standing together with “imperfect friends”

Interview with People’s March organizer on standing together with “imperfect friends”  Supreme Court refuses to defend constitutional right to organize

Supreme Court refuses to defend constitutional right to organize  Rural communities left behind by capitalism should look to socialism

Rural communities left behind by capitalism should look to socialism